The Transit Effect

Join “Jeopardy!” host Ken Jennings in a series on how transit shapes communities.

Ken Jennings, the host of “Jeopardy!” and the show’s record-breaking champion, has used public transit around the world. As a college student at UW, he regularly took the bus home to visit his family in Edmonds. Now, he’s partnering with Community Transit to explore how transit influences infrastructure, economies, culture, and opportunity in The Transit Effect, a seven-part video series.

Episode 1:

The History of Transit

In this first episode, Ken takes a deep dive into the power of public transit in shaping our past, present, and future.

Why should you care about public transit? Even if you never ride a bus or train, the transit systems around you influence how your community is built and how your day unfolds. It’s a force that shapes where we live, how we work, and who we connect with. To better understand how future transit investments might affect your world, there’s no better teacher than the past.

Sparking the Electric Age: America’s First Mass Transit Systems

Think electric transit is a modern idea? Think again. Electric mass transit shaped urban landscapes as far back as the late 1800s.

Through most of history, people relied on animals to do the heavy lifting. The first urbanized mass transit in the United States, the horse drawn Omnibus, came to New York in the 1820s. These large, enclosed stagecoaches followed fixed routes and schedules, much like modern buses. But poor road conditions made for a bumpy, uncomfortable, and slow-paced ride for passengers.

A mid-1800s image shows an Omnibus of the Fifth Avenue Stage Line in New York city.

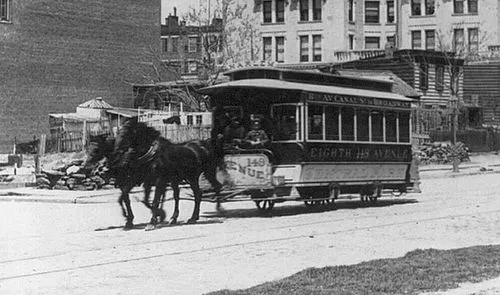

A decade later, streetcars pulled on rails embedded in city streets brought New Yorkers a more efficient transit option. Rail-assisted horsecars reduced friction and allowed for a smoother ride with less strain on the horses that powered them. Horsecars quickly spread to other major cities in the mid-1800s.

1895, the horse-drawn streetcar no. 148 of a New York City system, also known as the “horsecar.”

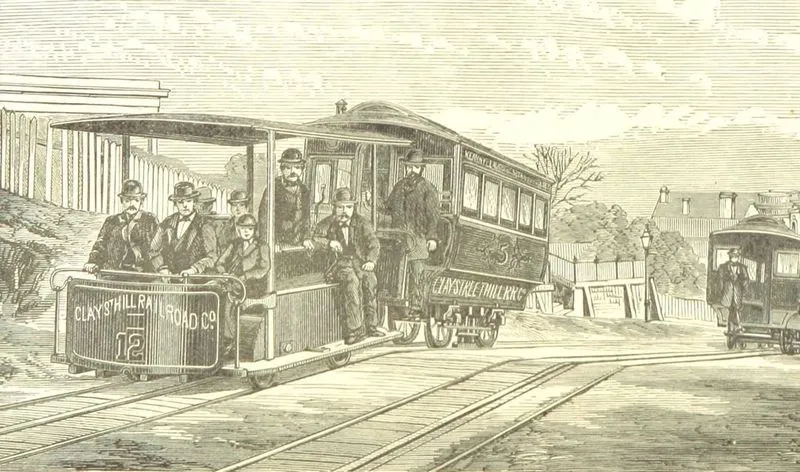

But relying on horses to pull heavy loads made traversing some terrains precarious. In 1869, civil engineer Andrew Smith Hallidie reportedly witnessed a team of horses collapse while struggling to pull a heavily loaded streetcar up a steep, wet hill in San Francisco. The incident became the driving force behind his quest to design a safer, mechanical transit system — what would become the cable car. Hallidie introduced the first successful cable car system in 1873. His design used a steam-powered underground cable to pull streetcars uphill — no horses required. So the next time you hear Tony Bennett croon about the city “where little cable cars climb halfway to the stars,” you’ll know he wasn’t just singing a romantic lyric — he was nodding to a 150-year-old transit innovation that helped shape San Francisco’s skyline and the future of urban travel.

Clay Street Hill Railroad in San Francisco was the world's first practical cable car system.

Steam-powered cable cars brought new challenges — they were expensive to build, difficult to maintain, and required central power stations that made them hard to scale. But the era of electrical innovation sparked new options for powering transit. Thomas Edison’s 1879 lightbulb was the first to be commercially successful, bringing electric lighting into homes and city streets. Nikola Tesla’s development of alternating current (AC) technology in the 1880s — later commercialized by George Westinghouse — made it possible to transmit electricity over long distances and power growing cities.

Postcard of electric trolley-powered streetcars of the Richmond Union Passenger Railway in Richmond, Virginia, in 1923, two generations after Frank J. Sprague successfully demonstrated his new system on the hills in 1888.

More than a dozen inventors tried — and failed — to build electric streetcar systems that worked reliably at scale before Frank J. Sprague’s breakthrough in 1888. Sprague’s system was the first to handle real-world city conditions — hills, curves, crowds, and all — with ease, using overhead wires and a single power source. The Richmond, Virginia network launched on February 2, 1888, with 10 cars and expanded to 40 within months, proving that fast, safe, and scalable electric transit was possible.

The result? Cities across the U.S. quickly adopted electric transit — streetcars, cable cars, and trolley —ushering in a new era of urban travel.

Comparison of Cable Cars, Electric Streetcars, and Trolleys

Electric streetcars didn’t just improve transit — they reshaped cities. With reliable service reaching farther out, urban areas expanded and gave rise to “trolley suburbs,” where people could live beyond city centers while staying connected. These early systems laid the groundwork for the modern public transit we rely on today, from subways to light rail.

Set in 1903, the 1944 film Meet Me in St. Louis starring Judy Garland captures the golden age of electric streetcars — so iconic to that era, they even got their own love song. Electric trolleys quickly became the backbone of public transportation in American cities at the turn of the century.

By the 1920s, there were 45,000 miles of transit track. Interurban operators, which provided electric railway services between cities, had laid approximately 18,000 miles of track by that same year.

Here in Snohomish County, people traveled on the Interurban Trolley between Seattle and Everett, roughly following the same path that is today known as the Interurban trail. The Interurban Trolley opened in 1910, running hourly passenger service and carrying freight over its 29-mile course. It became a key connector for small communities in Snohomish and King counties, transporting thousands of riders daily as well as freight for farmers and merchants in rural Snohomish County.

Interurban Trolley, Snohomish County

But the trolley didn’t last. The Great Depression (1929–1939) reduced travel overall and hit the Interurban’s revenues hard. Improved roads, the rise of the automobile, and bus competition added to a decline in ridership. The trolley’s service ended in February 1939, meeting the fate of many trolley lines across the county.

“I was four-and-a-half when I first boarded that high-flying interurban car, and never got over it!... The silvery bell and air-chime whistle, together with the gentle swing and sway of the big car and the clickety-clack on the rails made a rhythmic symphony of sound and motion, never to be duplicated by any other conveyance, before or since!”

– Kent L. Haley on riding the Interurban Trolley

For an up-close glimpse into Snohomish County’s transit past, you don’t need a ticket — just a good pair of walking shoes. When you bike or walk the Interurban Trail, you’re retracing the original path of the historic trolley line that once connected Seattle and Everett. And at Heritage Park in Lynnwood, you can tour the Interurban Car No. 55, a beautifully restored trolley rebuilt with original and refabricated parts. Open houses are held the first Saturday of each summer month, where local docents bring the story to life with historic details, fun facts, and a guided peek inside this electric-era time capsule.

America’s Love Affair with the Car

During the trolley’s heyday, another transportation innovation was revving up. Henry Ford’s Model T, introduced in 1908, put cars within reach for the average household thanks to mass production and falling prices. By the end of the 1920s, more than 23 million vehicles were on the road.

But the widespread adoption of cars hit a few red lights. The Great Depression of the 1930s made car ownership unaffordable for many, and World War II brought civilian auto production to a halt. Factories were converted for military use, gasoline and rubber were rationed, and transit became the go-to for daily travel once again.

Roadblocks Ahead: The Challenges of a Car-Centric World

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 put this love affair in overdrive, funding 41,000 miles of interstate highways and making it easier than ever to live far from where you worked. In the process, many cities dismantled streetcar systems, shifted investment away from transit, and prioritized roads and parking over walkability.

But that freedom came at a cost. Leaded gasoline, standard for decades, released toxic pollutants into the air, contributing to widespread public health and environmental damage. Traffic, smog, and sprawl became defining features of car-centric infrastructure.

According to the American Public Transportation Association (APTA), approximately 45% of Americans lack access to public transportation. This limited access to public transportation can be especially challenging for those without vehicles. About 9% of American households — 10 million households — do not own or have access to a car.

Without accessible and affordable transit options, people face barriers in reaching employment, education, healthcare, and other essential services. As populations grow and climate concerns rise, public transportation is regaining attention as a key part of sustainable urban planning.

And people, not cars, are driving these changes — advocating for walkable infrastructure and expansion of public transit, and trading in their car keys for ORCA cards.

The Return of Rail and the Future of Transit

Eighty-five years after the last Interurban trolley rolled through Snohomish County, electric mass transit is back on the rails — faster, farther, and built with sustainability in mind. With the opening of Sound Transit's Link light rail service to Lynnwood, the region is reconnecting by rail just as it did in the early 20th century.

By 2044, the Link light rail network will stretch across 116 miles and span 83 stations, connecting communities from Everett to Tacoma and Kirkland to Issaquah. It’s one of the most ambitious public transit expansions in the country.

Lynnwood City Center is the first station in Snohomish county to connect local bus riders to Link light rail.

A key part of that plan is the Everett Link Extension, which will is slated to bring 16 new miles of track and six additional station to Snohomish County by 2037 — making fast, reliable rail service available to thousands more residents and opening up new opportunities across the region.

Light rail trains are fully electric and powered by clean energy, including wind power, echoing the innovation of the early electric trolley while paving the way for a more connected and sustainable future.

“Often on our program we’ve ‘demystified’ things... I think it’s helpful for children to know that machines like trolleys don’t operate independently of people … that it’s people who make machines work.”

–Mr Rogers, Speaking about the trolley featured on his popular children's TV show

But light rail is just one part of the story.

Community Transit’s Swift bus rapid transit network helps people travel quickly and reliably along major corridors, with lines that connect directly to Link stations. Frequent local bus service brings people to jobs, schools, and neighborhoods across the county. And for shorter trips, Zip Shuttle offers on-demand service in some communities — bringing transit closer to home.

Together, these options form a modern, multimodal network that reflects how public transit has always shaped Snohomish County — linking people to opportunity, supporting local growth, and creating space for communities to thrive.

A century ago, electric trolleys sparked new ways of living. Today, transit is doing it again — just with better tools, cleaner energy, and more options than ever before.

Join the Conversation

Stay tuned for upcoming episodes as we continue to explore The Transit Effect and learn about public transit’s role in opportunity, sustainability, accessibility, and beyond. Subscribe and share your thoughts on our YouTube channel.